Why not just let the private sector deliver the mail

Currently FedEx, and UPS deliver the mail faster and better then the US Post Office despite a Federal law requiring that they charge 3 times what the US Post Office charges for the same services.Repeal that silly law and the private sector will almost certainly be able to deliver the mail, faster, better and cheaper then the US Post Office.

Tue, Jul 23, 2013, 1:33 PM EDT

Postal Service Moving Away From At-Your-Door Delivery

CNNMoney.comBy Jennifer Liberto | CNNMoney.com

If you're moving to a newly built house, say goodbye to mail delivery at your door.

And if some House Republicans get their way, all door-to-door mail delivery will go away.

The U.S. Postal Service is marching towards a more "centralized delivery," where residents pick up their own mail from clusters of mail boxes located in their neighborhood. Local postmasters are sending hundreds of letters to fast-growing communities, warning that cluster boxes will be the way mail will be delivered to new developments.

In the past year, the cash-strapped Postal Service has been asking companies in industrial parks and shopping malls to also adopt this form of mail delivery.

But Rep. Darrell Issa, the California Republican leading the House effort to save the postal service, wants more. He has made doing away with doorstep delivery a key part of his bill, which would require everyone to get mail at a curbside box or from a cluster box.

"A balanced approach to saving the Postal Service means allowing USPS to adapt to America's changing use of mail," said Issa, who is chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee.

Moving away from door-to-door delivery saves a lot of money. Right now, 35 million residences and businesses get mail delivered to their doorstep.

It costs $353 per stop for a delivery in most American cities, taking into account such things as salaries and cost of transport. By contrast, curbside mail box delivery costs $224, while cluster boxes cost $160, according to a report from the Postal Service's Office of Inspector General.

Delivering mail is the agency's largest fixed cost -- $30 billion. Ending such deliveries would save $4.5 billion a year. That's more than the $3 billion it would have saved from ending Saturday mail service, according to government reports.

That's why ending door delivery has drawn industry support from groups like the Greeting Card Association, which supports Saturday service.

But unions say it's a bad idea to end delivery to doorsteps and will be disruptive for the elderly and disabled. [but mostly to the high salaries of the over paid and under worked union members]

"It's madness," said Jim Sauber, chief of staff for the National Association of Letter Carriers. "The idea that somebody is going to walk down to their mailbox in Buffalo, New York, in the winter snow to get their mail is just crazy." [Well, not if a non-union, non-government postal worker can deliver the mail for a third or less what a US Postal employee can. Currently Federal law makes it illegal for the private sector to deliver mail unless they charge 3 that's THREE times what the US Post Office charges, or if they deliver the mail for free]

Yet postal officials say everything's on the table, when it comes to cost-cutting. [Well everything except letting the private sector compete with the US Post Office] Earlier this year, it tried to end Saturday mail delivery, but later reversed its decision.

The Postal Service continues to struggle with mail volume, especially drops in first-class mail, its big revenue driver, as more Americans move to electronic billing and e-mailing.

In 2012, the agency lost $16 billion. Last year, the agency twice defaulted on payments owed to the federal government to prefund retiree health care benefits totaling $11 billion. The agency has also exhausted a $15 billion line of credit from the U.S. Treasury.

Ending a Congressional mandate to make large annual payments toward retiree health care benefits would help solve the agency's woes.

As it awaits for help from Congress, the postal agency has been trying to do what it can on its own. One of the initiatives is pushing cluster boxes on new developments.

"Prior to this spring, we'd work with the construction companies and they could decide if the houses would get cluster boxes or curbline delivery --- now the Postal Service makes that decision," said Postal Service spokeswoman Sue Brennan.

In Cranberry, Pa., the community is up in arms after getting a letter in April from the Postal Service saying cluster boxes would be going in new developments.

Community leaders say they understand the boxes are cheaper but they want a better plan that takes into account safety, access and maintenance. Township leaders and the postal service are holding talks over the boxes.

"We understand what's driving this is a cost savings," said Cranberry Township Manager Jerry Andree. "But you can't just take a cluster box and drop it into the community without planning for its safety, use and access."

Harassment claim is latest blow to San Diego mayor

Associated Press Tue Jul 23, 2013 7:33 PM

SAN DIEGO — Irene McCormack Jackson says she endured months of harassment from Mayor Bob Filner while serving as his communications director. The turning point came at a staff meeting in June when another top aide confronted the mayor over his behavior and quit.

“You are running a terrible office. You are treating women in a horrible manner. What you are doing may even be illegal,” Allen Jones, then Filner’s deputy chief of staff and a longtime confidante, is quoted saying in a sexual harassment lawsuit filed by McCormack.

McCormack chimed in, “I agree with Allen. You are horrible.” When the mayor challenged her for an example, she said she replied, “How about when you said that I should take my panties off and work without them.”

The episode is described in the lawsuit McCormack filed Monday against Filner, dealing another blow to San Diego’s first Democratic leader in 20 years. His own party appears split on his leadership, though many Democrats have joined Republicans in calling for the former 10-term congressman to resign less than eight months into a four-year term.

McCormack was the first person to publicly identify herself as a target of Filner’s advances, suing nearly two weeks after some of the mayor’s prominent former supporters said he sexually harassed women and demanded he resign.

A second woman, Laura Fink, told KPBS in an interview that aired Tuesday that Filner patted her buttocks at a campaign event when he was a congressman in February 2005. When an attendee told the congressman that Fink was working her tail off for him as deputy campaign manager, Filner allegedly told her to turn around, patted her, laughed, and said, “No, it’s still there!”

Fink, who is now a political consultant, wrote Filner at the time to ask that he apologize for “totally unacceptable” behavior, according to her email posted on KPBS’ website. She told KPBS that Filner told her he was sorry but never responded to the email.

A Filner spokeswoman, Lena Lewis, didn’t answer phone calls or immediately respond to an email seeking comment on Fink’s allegations.

Filner rejected McCormack’s claims in a brief statement Monday that once again signaled he had no plans to step down. He didn’t address any specific allegations.

“I do not believe these claims are valid. That is why due process is so important. I intend to defend myself vigorously and I know that justice will prevail,” he said.

McCormack worked for nine years at the Port of San Diego, most recently earning $175,000 a year as vice president of public policy, and was previously a journalist for 25 years. She took an annual pay cut of $50,000 to join Filner’s inner circle in January.

U-T San Diego, the city’s dominant newspaper and her onetime employer, editorialized that she came across as “composed and highly credible” at a news conference Monday with her high-profile attorney, Gloria Allred.

“She is well-known, liked and respected in the city’s political, business and media circles,” the newspaper wrote in an editorial that concluded, “Unless there is a dramatic development helping Filner, we suspect the conventional wisdom about the difficulty of mounting a successful mayoral recall will soon change.”

The lawsuit brought renewed calls from two city councilmen for Filner to step aside. Kevin Faulconer and Todd Gloria said the mayor’s office was paralyzed.

“This is taking critical attention from the issues that affect San Diego families,” said Gloria, a Democrat who, as council president, would be interim mayor if Filner resigned.

McCormack says in her lawsuit filed in San Diego Superior Court that the leader of the nation’s eighth-largest city demanded kisses and dragged her around in headlocks while whispering sexual advances.

In February, he allegedly put McCormack in a headlock while they rode an elevator with a police officer who was adjusting his handcuffs, prompting him to tell her, “You know what I would like to do with those handcuffs?” On another elevator ride, Filner allegedly said, “Wouldn’t it be great if you took off your panties and worked without them on?”

The lawsuit says Filner asked McCormack to marry him, including once while he had her in a strong headlock during a doughnut break at a constituent event in April. The 70-year-old divorced man was engaged at the time to Bronwyn Ingram, who announced this month that she ended the relationship.

While reviewing a draft press release in June, Filner allegedly asked McCormack for a kiss and said, “I am infatuated with you. When are you going to get naked?” When she asked him to leave her office, the lawsuit says he responded, “I can go anywhere I want, any time I want.”

No one had publicly identified herself as a target of Filner’s advances until Monday. Last week, former supporters said Filner forcibly kissed a campaign volunteer on a public sidewalk and groped her in her car. Another constituent who attended a mayoral event at City Hall said Filner took her to an enclosed area, dismissed a staff member, asked her on a date and kissed her, they said.

An employee who worked for the mayor for six months complained that Filner grabbed her buttocks and touched her chest, according to the former supporters.

McCormack, who now works for the city in a job that doesn’t report to the mayor, said she saw Filner “place his hands where they did not belong on numerous women.” Her lawsuit said, without elaborating, that three women had to be driven home because of his “abusive treatment” and five schedulers resigned over his behavior.

After the initial allegations surfaced, Filner apologized for disrespecting and sometimes intimidating women. “I need help,” he declared.

On Friday, he welcomed the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department’s decision to open a hotline to take calls from any possible victims of his misconduct, saying “some of these allegations will finally be addressed by an appropriate investigative authority rather than by press conference and innuendo.”

This article is a great example of how to really screw things up it takes government idiots.

227,000 Names on List Vie for Rare Vacancies in City’s Public Housing

By MIREYA NAVARRO

Published: July 23, 2013

Lottie Mitchell made her regular pilgrimage the other week, riding the subway for 45 minutes, then transferring to a bus to reach her destination: an office of the New York City Housing Authority.

When her turn came, Ms. Mitchell, 57, using a cane, hobbled to the counter with the same request that she has made for the last four years.

“I want to check the status on my housing,” she said.

As always, the clerk responded: “You’re on the waiting list.”

It is called the Tenant Selection and Assignment Plan, but to hundreds of thousands of New Yorkers seeking a home, it is “the list.”

Prosperous city residents may consider public housing to be a place of last resort. The waiting list indicates otherwise.

The growth in the list — and the stories of those who struggle to move up on it to gain subsidized apartments — underscores how the city continues to face a shortage of housing for the poor and the working class.

There are now 227,000 individuals and families on the waiting list for Housing Authority apartments, totaling roughly half a million people, and the queue moves slowly. The apartments are so coveted that few leave them. Only 5,400 to 5,800 open up annually.

The odds, never good, are getting worse. This year, after the agency began accepting applications online, the waiting list reached a milestone: for the first time, the number of applicants exceeded the 178,900 apartments in the public housing stock.

“It’s become harder and harder to be able to afford a rental unit in the open market,” said Victor Bach, a senior housing policy analyst with the Community Service Society, a research and advocacy group for the poor. “Whether employment is up or down, the rents keep rising inexorably.”

Federal law prevents housing authorities from building additional units. With federal aid declining, the New York City agency also faces difficulty maintaining the projects that it has.

The average monthly rent for a public housing apartment is $436, officials said. The average household’s income is $23,000. (Tenants are required to pay up to 30 percent of their household income in rent.)

But low income alone does not determine who gets an apartment, and the waiting list is not run on a first-come-first-served basis.

Officials favor groups of applicants in order to further policy goals. Some, like victims of domestic violence, are given priority. Others, like working families, are preferred because they can pay higher rents and also help diversify the projects so they do not segregate the poor.

Those with a high priority can jump the line and may get an apartment in as little as three months. Others will wait years — with little if any prospect of getting off the list.

In 2005, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg took away preferences for homeless people staying in city shelters, arguing that the policy was an incentive for them to enter the shelter system in order to obtain public housing more easily.

As a result, the number of homeless families who enter public housing from shelters dropped to about 100 last year from an average of 1,600 a year before the policy changed, according to city figures.

Waiting times also depend on the type of apartment. An applicant who needs a two-bedroom will be on the list for less time than a single person who needs a studio, because only 3.5 percent of the authority’s apartments are studios, compared with 48 percent that have two bedrooms.

Manhattan is more difficult to move into because of high demand and because there is not as much public housing as in other boroughs. Staten Island is the easiest.

Ms. Mitchell has been on the waiting list since 2009. Once, she got plucked from the line for an eligibility interview.

“We were so excited,” said Ms. Mitchell, who lives with her 35-year-old disabled son in a city homeless shelter. “They said they’d call me back real soon.”

That was a year and a half ago.

Since then, Ms. Mitchell has gone twice a year to a Housing Authority office in the Bronx to check on her application.

She also has called. She has sent letters of reference. She has prodded the staffs of both the Bronx and Manhattan borough presidents to inquire on her behalf.

Still, an apartment remains out of reach.

Because some people can jump ahead, no one ever knows his or her place on the list or how long the wait will be.

“Every time I call, they don’t say anything,” said Maria Almonte, 42, who said she was behind in the rent for the $1,300-a-month, two-bedroom apartment she shares with two daughters in Washington Heights. Her monthly income of $1,800 is from child support, disability payments and food stamps.

“They say, ‘You’re on the waiting list, you’re on the waiting list,’ ” she said. “Sometimes I feel such anxiety because of the uncertainty.”

Applicants said they felt as if they were playing the lottery.

Kolaundria Gee, who lives in a shelter with her 3-year-old son while working full time at a day care center, said she checked on her application so often that she developed a rapport with an authority worker who answered her calls.

“He said to think positive,” Ms. Gee said. “Sometimes, we talked for up to two minutes.”

In May, she learned that the worker had retired.

“I cried,” Ms. Gee, 27, said. “With him, I felt a little hope.”

The most resourceful applicants turn to an ecosystem of helpers — legal aid lawyers, advocacy groups, borough president offices, City Council members — to try to move things along.

But advocates from several organizations said the most they could do was to get the authority to review an application to find out if any documents were missing, causing a holdup, or if the person forgot to include details that would mean a higher place on the list.

“They think I can get them an apartment faster,” said Councilwoman Rosie Mendez, the chairwoman of the subcommittee on public housing. “We tell them there’s no way.”

In a few cases, people have forged police and financial records to gain an edge, housing officials said.

But the officials maintained that their computerized system helps deter corruption.

“People can’t manipulate the list,” said Alan Pelikow, assistant director in the office of resident policy and administration. “It assures that people get a fair shake at housing.”

But any change in circumstance — losing a job, gaining a job, having a baby — can shift a priority, or affect eligibility for an available apartment of a certain size.

Hurricane Sandy showed how precarious a place in the line can be. To respond to the emergency, city officials temporarily froze the waiting list this year and set aside 470 apartments for evacuees who lost their homes.

When she had her eligibility interview in 2011, Ms. Mitchell was stunned to learn that because she had stopped working for health reasons between the date she applied for an apartment and the interview, she and her son were downgraded a notch — from homeless working family to just plain homeless — and lost an edge.

On her visit to the Housing Authority’s customer center in the Bronx last month, the woman on the other side of the counter looked at her computer and told Ms. Mitchell that her application had expired in April.

She asked how much time she had to reapply, to avoid losing her place on the list. Probably six months, the worker said. (In fact, the grace period is only 30 days, housing officials said.)

Later, Ms. Mitchell, who suffers from scoliosis, seemed deflated but no less persistent.

“You have to find out the hard way,” she said. “You really have to stay on top of it yourself or you lose it.”

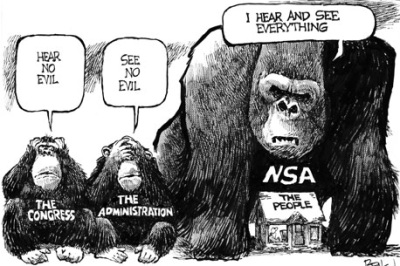

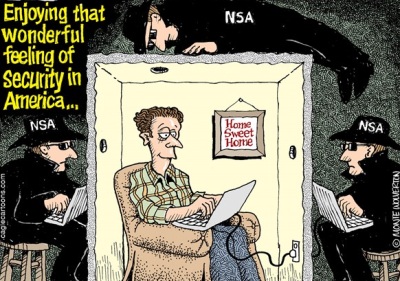

Last this is a damn good example of why we need the Second Amendment,

which is our right to keep and bear arms. The politicians and government bureaucrats

can't be trusted to obey the Constitution and the "people" need to have some means

to force them to.

State attorney argues legislators can ignore voter-mandated education funding law

Posted: Tuesday, July 23, 2013 1:26 pm | Updated: 2:16 pm, Tue Jul 23, 2013.

By Howard Fischer, Capitol Media Services | 0 comments

PHOENIX — Legislators are free to ignore a voter mandate to boost education funding each year to account for inflation, an attorney for the state told the Arizona Supreme Court on Tuesday.

Kathleen Sweeney, an assistant attorney general, conceded voters did approve the inflation adjustment in 2000, and she also did not dispute that the Arizona Constitution prohibits legislators from repealing or altering voter-approved laws.

But Sweeney, seeking to allow the Legislature to disregard the 2000 law, told the justices voters had no constitutional right to enact the funding mandate in the first place.

That brought a somewhat surprised reaction from Chief Justice Rebecca Berch. She pointed out it was the Legislature that put the inflation adjustment provision on the ballot in the first place.

"They got the voters to vote on their bad language,'' she said. “And now they're trying to disavow their bad language.''

Sweeney did not exactly contest the question of whether lawmakers essentially had pulled a fast one on voters, getting them to approve a law that had no legal standing.

"Perhaps, your honor,'' she replied to Berch.

And Sweeney gave essentially the same response to a query by Justice John Pelander, who asked if she was arguing that the 2000 vote was "a fruitless, useless act.''

The fight most immediately affects whether lawmakers are required to annually adjust education funding.

That 2000 ballot measure boosted the state's 5-percent sales tax by six-tenths of a cent. It also requires the Legislature to increase funding for schools by 2 percent or the change in the gross domestic price deflator, whichever is less.

Lawmakers did that until the 2010 when, facing a budget deficit, they reinterpreted what the law requires. The result is that, since then, schools have lost anywhere from $189 million to $240 million, depending on whose figures are used. Don Peters, representing several school districts, filed suit.

Legislators did add $82 million in inflation funding for the new fiscal year that began July 1 after the state Court of Appeals sided with challengers. But they are hoping the Supreme Court concludes that mandate is legally unenforceable.

The outcome of this fight has larger implications — and not only for future education funding. It also could set the precedent for what voters have the right to tell the Legislature to do.

Sweeney argued there are limits, despite the constitutional right of voters to approve their own laws and despite the Voter Protection Act that shields these laws from legislative tinkering.

She said the 2000 measure sets the formula for increasing state aid — and then tells the Legislature to find the money from somewhere. Sweeney argued that infringes on the constitutional right of lawmakers to decide funding priorities.

Justice Scott Bales pointed out the inflation formula is a statute. He said while it was enacted by voters, it should have the same legal status as a law approved by legislators themselves.

"Do you think the Legislature can simply ignore statutes providing that it shall do certain things?'' he asked.

"Yes,'' Sweeney responded.

Peters disagreed.

"The statute that requires inflation adjustments is the law,'' he told the justices. “The Legislature has to obey the law like all the rest of us.''

And Peters said the constitutional Voter Protection Act precludes the Legislature from altering that law without first asking voter permission.

"Therefore, it must do what the statute required unless the people change it,'' he said.

Pelander questioned whether there are limits on what voters can tell the Legislature to do. Peters responded that the Arizona Constitution gives voters broad powers to make their own laws as long as those measures do not "offend'' other state or federal constitutional provisions.

"So they can do pretty much anything they want to,'' Peters told the justices. “And that includes giving instructions to the Legislature.''

Peters acknowledged the Supreme Court has previously said a law approved by one Legislature cannot bind future lawmakers.

But he argued that, as far as voter-approved laws, all that changed in 1998 with enactment of the Voter Protection Act.

"That balance of power is different,'' Peters said.

The justices gave no indication when they will rule.

Peters acknowledged after Tuesday's hearing that he could win his legal argument and still have a problem.

The high court could rule that lawmakers cannot ignore the 2000 law. But the justices have consistently refused to actually order the Legislature to find the additional dollars to fully fund the formula.

That could result in a situation where schools get the higher per-student funding as the formula requires, at least until the cash appropriated by the Legislature runs out. But Peters said he doubts lawmakers are willing to endure the wrath of voters if schools need to shut their doors before the end of the school year.

Last this is a damn good example of why we need the Second Amendment,

which is our right to keep and bear arms. The politicians and government bureaucrats

can't be trusted to obey the Constitution and the "people" need to have some means

to force them to.

State attorney argues legislators can ignore voter-mandated education funding law

Posted: Tuesday, July 23, 2013 1:26 pm | Updated: 2:16 pm, Tue Jul 23, 2013.

By Howard Fischer, Capitol Media Services | 0 comments

PHOENIX — Legislators are free to ignore a voter mandate to boost education funding each year to account for inflation, an attorney for the state told the Arizona Supreme Court on Tuesday.

Kathleen Sweeney, an assistant attorney general, conceded voters did approve the inflation adjustment in 2000, and she also did not dispute that the Arizona Constitution prohibits legislators from repealing or altering voter-approved laws.

But Sweeney, seeking to allow the Legislature to disregard the 2000 law, told the justices voters had no constitutional right to enact the funding mandate in the first place.

That brought a somewhat surprised reaction from Chief Justice Rebecca Berch. She pointed out it was the Legislature that put the inflation adjustment provision on the ballot in the first place.

"They got the voters to vote on their bad language,'' she said. “And now they're trying to disavow their bad language.''

Sweeney did not exactly contest the question of whether lawmakers essentially had pulled a fast one on voters, getting them to approve a law that had no legal standing.

"Perhaps, your honor,'' she replied to Berch.

And Sweeney gave essentially the same response to a query by Justice John Pelander, who asked if she was arguing that the 2000 vote was "a fruitless, useless act.''

The fight most immediately affects whether lawmakers are required to annually adjust education funding.

That 2000 ballot measure boosted the state's 5-percent sales tax by six-tenths of a cent. It also requires the Legislature to increase funding for schools by 2 percent or the change in the gross domestic price deflator, whichever is less.

Lawmakers did that until the 2010 when, facing a budget deficit, they reinterpreted what the law requires. The result is that, since then, schools have lost anywhere from $189 million to $240 million, depending on whose figures are used. Don Peters, representing several school districts, filed suit.

Legislators did add $82 million in inflation funding for the new fiscal year that began July 1 after the state Court of Appeals sided with challengers. But they are hoping the Supreme Court concludes that mandate is legally unenforceable.

The outcome of this fight has larger implications — and not only for future education funding. It also could set the precedent for what voters have the right to tell the Legislature to do.

Sweeney argued there are limits, despite the constitutional right of voters to approve their own laws and despite the Voter Protection Act that shields these laws from legislative tinkering.

She said the 2000 measure sets the formula for increasing state aid — and then tells the Legislature to find the money from somewhere. Sweeney argued that infringes on the constitutional right of lawmakers to decide funding priorities.

Justice Scott Bales pointed out the inflation formula is a statute. He said while it was enacted by voters, it should have the same legal status as a law approved by legislators themselves.

"Do you think the Legislature can simply ignore statutes providing that it shall do certain things?'' he asked.

"Yes,'' Sweeney responded.

Peters disagreed.

"The statute that requires inflation adjustments is the law,'' he told the justices. “The Legislature has to obey the law like all the rest of us.''

And Peters said the constitutional Voter Protection Act precludes the Legislature from altering that law without first asking voter permission.

"Therefore, it must do what the statute required unless the people change it,'' he said.

Pelander questioned whether there are limits on what voters can tell the Legislature to do. Peters responded that the Arizona Constitution gives voters broad powers to make their own laws as long as those measures do not "offend'' other state or federal constitutional provisions.

"So they can do pretty much anything they want to,'' Peters told the justices. “And that includes giving instructions to the Legislature.''

Peters acknowledged the Supreme Court has previously said a law approved by one Legislature cannot bind future lawmakers.

But he argued that, as far as voter-approved laws, all that changed in 1998 with enactment of the Voter Protection Act.

"That balance of power is different,'' Peters said.

The justices gave no indication when they will rule.

Peters acknowledged after Tuesday's hearing that he could win his legal argument and still have a problem.

The high court could rule that lawmakers cannot ignore the 2000 law. But the justices have consistently refused to actually order the Legislature to find the additional dollars to fully fund the formula.

That could result in a situation where schools get the higher per-student funding as the formula requires, at least until the cash appropriated by the Legislature runs out. But Peters said he doubts lawmakers are willing to endure the wrath of voters if schools need to shut their doors before the end of the school year.

Personally I am against the death penalty, because mistakes have been made and innocent people have been executed.

But still I find it ridiculously silly that the FDA must approve drugs that are used to murder people as being safe????

The real question is now will anybody that helped execute Jeffrey Landrigan be punished for using an "unsafe" drug to murder him with????

I suspect this silliness is a good indication that government is more about providing high paying do nothing jobs for our government masters then serving the people.

Last but not least isn't this the same Federal government that says marijuana is an absolutely useless drug with absolutely not medical use? And that marijuana is a dangerous drug that is addictive and will kill you.

Court: FDA erred in allowing Arizona to import execution drugs

By Michael Kiefer The Republic | azcentral.com Tue Jul 23, 2013 5:20 PM

A U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., has upheld a lower-court ruling that the Food and Drug Administration broke the law by allowing Arizona and two other states to illegally import drugs used to carry out executions by lethal injection.

In October 2010, days before Arizona inmate Jeffrey Landrigan was to be executed, The Arizona Republic revealed that the state corrections department had obtained some of the execution drugs from overseas.

The FDA insisted there was no legal mechanism to import the drug, a fast-acting barbiturate named sodium thiopental. The Arizona Department of Corrections denied it had obtained the drug illegally.

Landrigan was executed with the drug.

By December of that year, the FDA changed its story and claimed it would exercise “enforcement discretion” and not enforce laws prohibiting the drug’s import. Meanwhile, the British and Italian governments banned the export of thiopental for executions.

Freedom of Information Act requests by The Republic and others later revealed that the FDA officials and the White House were aware of and facilitating the imports.

But in June 2011, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Adminstration told the Arizona Department of Corrections that it could no longer use thiopental, one day before it was to execute murderer Donald Beaty. The execution was performed using the drug pentobarbital.

Then, in March 2012, reacting to a lawsuit filed on behalf of death-row prisoners in Arizona, California and Tennessee, a U.S. District Court Judge in Washington, D.C., ruled that the FDA had violated the law by allowing those states to bypass regulations to import the unapproved drugs for executions.

The FDA appealed the ruling on the grounds that its ability to admit and reject drug shipments into the country is not subject to judicial review and that it indeed has enforcement discretion. Part of that discretion, it argued, was to deal with domestic shortages, as had occurred with thiopental, an older-generation drug used for anesthesia.

Because the FDA had not tested or analyzed the imported drug, and because there was no mechanism for its import, it was classified under law as an unbranded or unapproved new drug.

The three Arizona plaintiffs initially named in the federal lawsuit, Beaty, Eric King and Daniel Cook, have all been executed since the lawsuit was filed.

The Court of Appeals affirmed the lower-court decision, stating that the FDA has duties under the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act, and that “The FDA acted in derogation of those duties by permitting the importation of thiopental, a concededly misbranded and unapproved new drug, and by declaring that it would not in the future sample and examine foreign shipments of the drug despite knowing they may have been prepared in an unregistered establishment.”

The Court of Appeals, however, vacated the lower-court ruling that the FDA collect all remaining quantities of the drug that had been allowed into the country.

By and large, thiopental has been replaced in clinical settings by the newer drug propofol. Arizona and most other states that carry out execution by lethal injection now use pentobarbital, but the European manufacturer of that drug has curtailed sales for executions, and the Arizona supply has reportedly passed its expiration date.

Key Homeland official facing ethics inquiry

By Alicia A. Caldwell Associated Press Tue Jul 23, 2013 10:31 PM

WASHINGTON — President Barack Obama’s choice to be the No. 2 official at the Homeland Security Department is under investigation for his role in helping a company run by a brother of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, the Associated Press has learned.

Alejandro Mayorkas, director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, is being investigated for his role in helping the company secure an international investor visa for a Chinese executive, according to congressional officials briefed on the investigation. The officials spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to release details of the investigation.

Mayorkas was named by Homeland Security’s Inspector General’s Office as a target in an investigation involving the foreign investor program run by USCIS, according to an e-mail sent to lawmakers late Monday.

In that e-mail, the IG’s office said, “At this point in our investigation, we do not have any findings of criminal misconduct.” The e-mail did not specify any criminal allegations it might be investigating.

White House press secretary Jay Carney referred questions to the inspector general’s office, which said that the probe is in its preliminary stage and that it doesn’t comment on the specifics of investigations.

The program, known as EB-5, allows foreigners to get visas if they invest $500,000 to $1 million in projects or businesses that create jobs for U.S. citizens. The amount of the investment required depends on the type of project. Investors who are approved for the program can become legal permanent residents after two years and can later be eligible to become citizens.

If Mayorkas were confirmed as Homeland Security’s deputy secretary, he probably would run the department until a permanent replacement was approved to take over for departing Secretary Janet Napolitano.

The e-mail to lawmakers said the primary complaint against Mayorkas was that he helped a financing company run by Anthony Rodham, a brother of Hillary Clinton, to win approval for an investor visa, even after the application was denied and an appeal was rejected.

Mayorkas, a former U.S. attorney in California, previously came under criticism for his involvement in the commutation by President Bill Clinton of the prison sentence of the son of a Democratic Party donor. Another of Hillary Clinton’s brothers, Hugh Rodham, had been hired by the donor to lobby for the commutation. Mayorkas told lawmakers during his 2009 confirmation hearing that “it was a mistake” to talk to the White House about the request.

Hillary Clinton, who stepped down as secretary of State on Feb. 1, is considered a possible contender for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2016.

According to the Inspector General’s e-mail, the investigation of the investor visa program also includes allegations that other USCIS Office of General Counsel officials obstructed an audit of the visa program by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The e-mail did not name any specific official from the general counsel’s office.

The e-mail says investigators did not know whether Mayorkas was aware of the investigation. The FBI’s Washington Field Office was told about the investigation in June after it inquired about Mayorkas as part of the White House background investigation for his nomination as deputy DHS secretary.

The FBI in Washington has been concerned about the investor visa program and the projects funded by foreign sources since at least March, according to e-mails obtained by the AP.

The bureau wanted details of all of the limited liability companies that had invested in the EB-5 visa program. Of particular concern, the FBI official wrote, was Chinese investment in projects, including the building of an FBI facility.

“Let’s just say that we have a significant issue that my higher ups are really concerned about and this may be addressed way above my pay grade,” an official wrote in one e-mail. The FBI official’s name was redacted in that e-mail.

Iowa Sen. Charles Grassley, the ranking Republican on the Senate Judiciary Committee, sent the FBI a lengthy letter Tuesday asking for details of its review of the foreign investor visa program and Chinese investment in U.S. infrastructure projects.

Chinese investment in infrastructure projects has long been a concern of the U.S. government. In September, the Obama administration blocked a Chinese company from owning four wind farm projects in northern Oregon that were near a Navy base used to fly unmanned drones and electronic-warfare planes on training missions. And in October, the House Intelligence Committee warned that two leading Chinese technology firms, Huawei Technologies Ltd. and ZTE Corp., posed a major security threat to the U.S. Both firms have denied being influenced by the Chinese government.

The most routine users of the EB-5 program are Chinese investors. According to an undated, unclassified State Department report about the program obtained by the AP, the U.S. Consulate in Guangzhou, China, processed more investor visas in the 2011 fiscal year than any other consulate or embassy. The document says “applicants are usually coached and prepped for their interviews, making it difficult to take at face value applicants’ claims” about where their money comes from and whether they hold membership in the Chinese Communist Party. Party membership would make an applicant ineligible for the investor visa.

Anthony Rodham is president and CEO of Gulf Coast Funds Management LLC in McLean, Va. The firm is one of hundreds of “Regional Centers” that pool investments from foreign nationals looking to invest in U.S. businesses or industries as part of the foreign investor visa program.

There was no immediate response to an e-mail sent to Gulf Coast requesting comment.

It is unclear from the IG’s e-mail why the investor visa application was denied. Visa requests can be denied for a number of reasons, including a circumstance where an applicant has a criminal background or is considered a threat to national security or public safety.

How a secretive panel uses data that distorts doctors’ pay

By Peter Whoriskey and Dan Keating, Published: July 20 E-mail the writers

When Harinath Sheela was busiest at his gastroenterology clinic, it seemed he could bend the limits of time.

Twelve colonoscopies and four other procedures was a typical day for him, according to Florida records for 2012. If the American Medical Association’s assumptions about procedure times are correct, that much work would take about 26 hours. Sheela’s typical day was nine or 10.

“I have experience,” the Yale-trained, Orlando-based doctor said. “I’m not that slow; I’m not fast. I’m thorough.”

This seemingly miraculous proficiency, which yields good pay for doctors who perform colonoscopies, reveals one of the fundamental flaws in the pricing of U.S. health care, a Washington Post investigation has found.

Unknown to most, a single committee of the AMA, the chief lobbying group for physicians, meets confidentially every year to come up with values for most of the services a doctor performs.

Those values are required under federal law to be based on the time and intensity of the procedures. The values, in turn, determine what Medicare and most private insurers pay doctors.

But the AMA’s estimates of the time involved in many procedures are exaggerated, sometimes by as much as 100 percent, according to an analysis of doctors’ time, as well as interviews and reviews of medical journals.

If the time estimates are to be believed, some doctors would have to be averaging more than 24 hours a day to perform all of the procedures that they are reporting. This volume of work does not mean these doctors are doing anything wrong. They are just getting paid at the rates set by the government, under the guidance of the AMA.

In fact, in comparison with some doctors, Sheela’s pace is moderate.

Take, for example, those colonoscopies.

In justifying the value it assigns to a colonoscopy, the AMA estimates that the basic procedure takes 75 minutes of a physician’s time, including work performed before, during and after the scoping.

But in reality, the total time the physician spends with each patient is about half the AMA’s estimate — roughly 30 minutes, according to medical journals, interviews and doctors’ records.

Indeed, the standard appointment slot is half an hour.

To more broadly examine the validity of the AMA valuations, The Post conducted interviews, reviewed academic research and conducted two numerical analyses: one that tracked how the AMA valuations changed over 10 years and another that counted how many procedures physicians were conducting on a typical day.

It turns out that the nation’s system for estimating the value of a doctor’s services, a critical piece of U.S. health-care economics, is fraught with inaccuracies that appear to be inflating the value of many procedures:

●To determine how long a procedure takes, the AMA relies on surveys of doctors conducted by the associations representing specialists and primary care physicians. The doctors who fill out the surveys are informed that the reason for the survey is to set pay. Increasingly, the survey estimates have been found so improbable that the AMA has had to significantly lower them, according to federal documents.

●The AMA committee, in conjunction with Medicare, has been seven times as likely to raise estimates of work value than to lower them, according to a Post analysis of federal records for 5,700 procedures. This happened despite productivity and technology advances that should have cut the time required.

●If AMA estimates of time are correct, hundreds of doctors are working improbable hours, according to an analysis of records from surgery centers in Florida and Pennsylvania. In some specialties, more than one in five doctors would have to have been working more than 12 hours on average on a single day — much longer than the 10 hours or so a typical surgery center is open.

Florida records show 78 doctors — gastroenterologists, ophthalmologists, orthopedic surgeons and others — who performed at least 24 hours worth of procedures on an average workday.

Some former Medicare chiefs say the problem arises from giving the AMA and specialty societies too much influence over physician pay. Hospital fees are determined separately.

“What started as an advisory group has taken on a life of its own,” said Tom Scully, who was Medicare chief during the George W. Bush administration and is now a partner in a private equity firm that invests in health care. “The idea that $100 billion in federal spending is based on fixed prices that go through an industry trade association in a process that is not open to the public is pretty wild.”

He said that, every now and again, former Medicare chiefs — Republicans and Democrats — gather for a lunch and that, when they do, they agree that the process is, at best, unseemly.

“The concept of having the AMA run the process of fixing prices for Medicare was crazy from the beginning,” Scully said. “It was a fundamental mistake.”

In response, the chair of the AMA committee that sets the values, Barbara Levy, a physician, acknowledged that “all of the times are inflated by some factor” — though not by the same amount.

But she defended the accuracy of the values assigned to procedures, saying that the committee is careful to make sure that the relative values of the procedures are accurate — that is, procedures involving more work are assigned larger values than those that involve less. It is up to Congress and private insurers then to assign prices based on those values.

“None of us believe the numbers are fine-tuned,” Levy said. “We do believe we get them right with respect to each other.”

Moreover, the committee has reduced the valuations of more than 400 procedures in recent years to address such concerns, AMA officials said.

Over that time, Medicare officials have increasingly looked askance at the AMA estimates.

But even though the AMA figures shape billions in federal Medicare spending and billions more in spending from private insurers, the government is ill-positioned to judge their accuracy.

For one thing, the government doesn’t appear to have the manpower. The government has about six to eight people reviewing the estimates provided by the AMA, government officials said, but none of them do it full time.

By contrast, hundreds of people from the AMA and specialty societies contribute to the AMA effort. The association “conservatively” has estimated the costs of developing the values at about $7 million in time and expense annually. The AMA and the medical societies, not the government, develop the raw data upon which the analysis is based.

Over the past decade, Medicare’s payments to doctors have risen quickly. Medicare spending on physician fees per patient grew 58 percent between 2001 and 2011, mostly because doctors increased the number of procedures performed but also because the price of those procedures rose, according to MedPAC, an independent federal agency that advises Congress about Medicare.

Members of the public may attend committee meetings if they get the approval of the chairman, but even when they’re invited, attendees must sign a confidentiality agreement. That is meant to prevent interim decisions from spurring inappropriate market speculation and industry confusion, AMA officials said.

Other groups that make recommendations to the government are governed by the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which requires that meetings be public and that documents be publicly available. But those requirements do not apply to the AMA committee, officials said, because the AMA is not formally considered an advisory committee.

Even so, the committee’s influence on federal spending over time has been expansive: In some years, Medicare officials have accepted the AMA numbers at rates as high as 95 percent.

****

The fundamental question is difficult, even philosophically: What should a doctor make?

The forces that normally determine prices — haggling between buyers and sellers — often don’t apply in health care. Prices are hard to come by; insurers do most of the buying; sick patients are unlikely to shop around much.

At its inception, the Medicare system paid doctors what was described as “usual, customary and reasonable” charges. But that vague standard was soon blamed for a rapid escalation in physician fees.

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, the United States called on a group at Harvard University to develop a more deliberate system for paying doctors.

What they came up with, basically, is the current point system. Every procedure is assigned a number of points — called “relative value units” — based on the work involved, the staff and supplies, and a smaller portion for malpractice insurance.

Every year, Congress decides how much to pay for each point — this year, for example, the government initially assigned $34.02 per point, though prices vary somewhat with location and other factors.

This point system is critical in U.S. health-care economics because it doesn’t just rule Medicare payments. Roughly four out of five insurance companies use the point system for the basis of their own physician fees, according to the AMA. The private insurers typically pay somewhat more per point than does Medicare.

Once the system developed by the Harvard researchers was initiated, however, the Medicare system faced a critical problem: As medicine evolved, the point system had to be updated. Who could do that?

The AMA offered to do the work for free.

Today, the 31-member AMA committee that makes the update recommendations to Medicare — it is known as the Relative Value Update Committee, or RUC — consists of 25 members appointed by medical societies and six others. The chair is appointed by the AMA.

To inform its decisions, the committee relies on surveys submitted by the relevant professional societies. For example, in setting the value for a colonoscopy, the committee has turned to the American Gastroenterological Association and a similar group for information.

Typically, the surveys ask doctors about the time and intensity of the procedure under study.

The survey “is important to you and other physicians,” the standard form tells doctors, “because these values determine the rate at which Medicare and other payers reimburse.”

Sometimes the doctors within a specialty will overestimate the value of their work, Levy said. When that happens, the committee has increasingly decided to significantly lower their estimates of the work involved.

“Suppose I am a cardiologist, and I think I am the most important thing on Earth,” Levy said.

The RUC, she said, may have to say, “We know you’re really important but” you’ve overestimated the work involved on the survey.

“The 31 voting people around that table can be really harsh,” Levy said. “Someone can come to us with data that looks skewed, and we tell them, ‘It doesn’t pass the smell test.’ ”

But critics of the AMA process, including former Medicare chiefs and the Harvard researchers who created the system, say that biased surveys and other conflicts of interest make the results unreliable.

In developing the point system, the Harvard researchers and the government made available their raw data and statistical methods and held public meetings; they also limited the role of the AMA and specialist societies, participants in that process said.

The AMA process is not so open.

The current set of values “seems to be distorted,” said William Hsiao, an economist at the Harvard School of Public Health who helped develop the point system. “The AMA fought very hard to take over this updating process. I said this had to be done by an impartial group of people. This is highly political.”

****

Federal law makes the importance of time explicit: The work points assigned to a procedure will reflect the “physician time and intensity in furnishing the service” and includes the physician’s time before, during and after a procedure. Every year, the Medicare system publishes its time estimates for every service, which are based on AMA surveys.

“Improving the accuracy of procedure time assumptions used in physician fee schedule ratesetting continues to be a high priority,” agency officials wrote last year. “Procedure time is a critical measure.”

To examine the plausibility of the estimated times, The Post analyzed the records for doctors who work in outpatient surgery clinics in Florida.

The doctors included ophthalmologists, hand surgeons, orthopedic surgeons and gastroenterologists.

The Post chose the outpatient surgery clinics for review because their surgery records for Medicare and private payers were publicly available. The calculations of physician time used by The Post are conservative because they do not include the procedures that the doctors performed at hospitals, where many such doctors also see patients. The counts also exclude secondary procedures performed on a given patient, as well as follow-up visits.

Even so, for this group of doctors, the time estimates made by Medicare and the AMA appear significantly exaggerated.

If the AMA time estimates are correct, then 41 percent of gastroenterologists, 23 percent of ophthalmologists and 17 percent of orthopedic surgeons were typically performing 12 hours or more of procedures in a day, which is longer than the typical outpatient surgery center is open, The Post found in the Florida data.

Additionally, if the AMA estimates are correct, more than 3 percent of ophthalmologists and internists and more than 2 percent of orthopedic surgeons are squeezing more than 24 hours of procedures into a single day.

Florida is not unique. In a similar review of nine endoscopy clinics in Pennsylvania, The Post found 25 of 59 doctors at nine Pennsylvania gastroenterology clinics performed an average 12 hours or more of procedure time at least one day per week, with two totaling over 24 hours, rates similar to the Florida pattern.

Ophthalmologist David Shoemaker is among the busiest doctors in Florida, performing 3,594 cataract surgeries and similar procedures last year. His workload of 30 to 40 surgeries per day on Mondays and Tuesdays amounts to 30-plus-hour workdays if AMA time estimates are correct. Yet he works about 101 / 2 hours those days.

Shoemaker’s seven locations of Centers for Sight have an all-in-one integration with testing, anesthesiology, preparation, surgery and post-operative care, said James Dawes, chief administration officer.

“We shun the word ‘assembly line,’ ” Dawes said. “We’re in the patient care business, and every patient is unique. Every eye is unique. We’ve worked hard to make sure it doesn’t feel like an assembly line.”

The finding that doctors are working much more quickly than AMA assumes is supported by research by MedPAC that shows that the actual times of surgery were quite a bit less than the AMA-Medicare estimates.

Using operating room logs, researchers calculated the average times of 60 key surgeries and invasive diagnostic procedures. For all but two of the procedures, the AMA estimates were longer. For example, while an abdominal hysterectomy took 138 minutes on average, the AMA said it takes nearly twice that long.

“Surgical times for other related services are likely to be overstated as well,” researchers Nancy McCall, Jerry Cromwell and Peter Braun concluded. Braun helped create the point system with Harvard’s Hsiao.

The AMA’s Levy said the committee has developed other ways to estimate values that don’t depend on time.

The critics don’t “get the concept of where the [committee] is in 2013,” Levy said. “We’ve evolved a bunch of processes that make them better than they were when Harvard did it.”

Whatever its methods, however, the AMA panel has been raising the work points for procedures.

Between 2003 and 2013, the AMA and Medicare have increased the work values for 68 percent of the 5,700 codes analyzed by The Post, while decreasing them for only 10 percent.

While advances in technology and skill should have reduced the amount of work required, the average work value for a code rose 7 percent over that decade, largely because officials raised the value of doctors’ visits. The rise came in addition to allowances for inflation and other economic factors.

When discussing the rise in the nation’s bills for physicians, AMA officials note that they only assign points to procedures — so the Medicare bill depends upon how much the federal government decides to spend for each point.

Officials determine that spending by several complex formulas laid out in federal rules. One of them forces Medicare to lower how much it pays per point when work values rise significantly. Every year since 2003, however, the other formulas have been overridden by Congress, which has adjusted the payments independently.

That means it’s difficult to definitively link the nation’s rising Medicare bill to the increasing work values set by the AMA. However, critics say the AMA’s time exaggerations undoubtedly help inflate the prices of many procedures.

Medicare officials have been trying to develop ways to more accurately quantify doctor work and are conducting two studies to refine its measurement.

The Medicare bureaucracy “takes into account a number of different factors and sources of information, including the RUC recommendations, when setting reimbursement rates for physicians,” said agency spokeswoman Tami S. Holzman. The acceptance rate of the AMA’s values has fallen in recent years from 90 percent to about 70 percent.

“We want to ensure that relative payment rates for physicians’ services are appropriate and fair,” she said.

****

Most people don’t time their own colonoscopies.

But Robert Berenson, a physician, a former Medicare official and now a fellow at the Urban Institute, has been a longtime skeptic of the time measurements.

When he had his own, Berenson checked his watch.

The actual procedure time — “scope in to scope out” — was exactly half of what Medicare estimates.

“It reminds me of the Marx Brothers line: ‘Who are you going to believe, me or your own eyes?’ ” Berenson said.

An estimated 15 million colonoscopies are performed annually in the United States, mainly to detect and prevent cancer in people older than 50. In the procedure, a tube with a video camera at the tip is inserted through the anus into the colon. Pictures from the inside appear on a screen.

In calculating how much should be paid for a procedure, the AMA and Medicare make some very specific time estimates.

For a colonoscopy, the total physician time is 75 minutes. This includes 25 minutes of evaluating and positioning the patient; five minutes for the physician to dress, scrub and wait; as well as 15 minutes afterward. The procedure itself is timed at 30 minutes.

Berenson counted 15 minutes in his own procedure.

Likewise, a New England Journal of Medicine article reported that in a study of 2,000 different colonoscopies, the average duration of the basic screening procedure was 13.5 minutes — not the 30 minutes estimated by the AMA. Similarly, it found that a colonoscopy with polyp removal took 18 minutes — as opposed to the 43 minutes estimated by the AMA.

The Post asked gastroenterologists if the procedure takes the 75 minutes estimated by the AMA.

“Of my time?” said Frederick Ruthardt, a gastroenterologists in Uniontown, Pa., shaking his head. He performed hundreds of them in 2011, according to state records. “That sounds pretty high.”

It is possible that in 1992, critics allow, when the price list was first developed, a colonoscopy actually took something close to 75 minutes. But in the decades since, the technology has undergone a revolution.

The tubular instruments are now far easier to move through the colon — the physician can stiffen or weaken the probe as necessary.

Meanwhile, digital technology has vastly improved the doctor’s view. In the early 1990s, doctors had to hunch over an eyepiece similar to that of a microscope for a look; now the images are displayed on a large screen in high-definition video.

“The evolution has saved labor and improved accuracy,” said David Barlow, who has worked on developing the devices for decades and is now a vice president at Olympus America.

Indeed, some doctors said it has cut the time and discomfort in half.

Yet despite these advances, the AMA and Medicare say the amount of work estimated in a colonoscopy essentially hasn’t budged. The work involved was 3.7 “relative value units” or points in the early 1990s; after more than two decades of labor-saving advances, it is still worth 3.7 points. The typical Medicare price including overhead is about $220.

The American Gastroenterology Association, a specialty group that advocates on behalf of the doctors who perform colonoscopies, said the number is justified despite the improvement in technology.

“The paradox is that we are spending more time than what you might assume,” said Joel V. Brill, a gastroenterologist who served as a liaison between the association and the RUC. “Things that you might not have been able to see through the scope, you can see now.”

Levy said the RUC is slated to review the code again in the coming year.

Two problems arise when some procedures are overvalued, according to the critics.

First, it means some patients and insurers are paying too much.

Second, doctors may be more likely to perform those procedures than they otherwise would be.

Indeed, while health experts worry that many people who should be getting colonoscopies are not, it appears that some patients are getting too many.

Average-risk patients who have a colonoscopy that shows no signs of trouble are not supposed to receive another for 10 years, according to Medicare guidelines.

But according to researchers at the University of Texas Medical School, about 46 percent of patients were getting another colonoscopy within seven years.

The finding, based on a review of 24,000 patient records and reported last year in the Archives of Internal Medicine, said that such colonoscopies were more likely to be performed by doctors rated as “high volume” providers.

One of the study’s authors, James S. Goodwin, a geriatrician at the University of Texas in Galveston, said doctors make decisions based on a large number of factors. But it’s foolish, he said, to ignore the financial angles.

“Economic incentives in medicine are like the force of gravity,” Goodwin said. “To pretend they don’t exist is crazy. They’re there.”

So how much does a physician make on a basic colonoscopy?

A good place to look is Pennsylvania, where the state tracks medical procedures and the profits of the doctor-owned surgery centers.

Even in an otherwise down-at-the-heels former coal town, the procedure can be big business.

At Schuylkill Endoscopy, located in a tidy green building behind the McDonald’s in Pottsville, Pa., three doctors performed thousands of colonoscopies in 2011, taking in more than $700,000, along with hundreds of thousands more for other similar procedures. On top of those physician fees, the endoscopy clinic, which is owned by two of the physicians and a management company, took in $1.5 million in operating profits in 2011, according to state records.

“I am very comfortable — very grateful,” said one of the owner-doctors, Amrit Narula, who lives in a modern-style, 5,000-square-foot house atop a ridge here.

Like other doctors interviewed for the story, Narula noted that he has no role in setting the Medicare value. He does not lobby Medicare and has never filled out one of the RUC surveys. He agreed that the time estimates in his field sound exaggerated.

By itself, the professional fee for a colonoscopy makes him about $260 an hour after his expenses. (That’s a figure that’s based on the clinics’ mix of patients and the Medicare assumptions about overhead.)

Is that too much? In the past, the loudest criticism of the point system has come from primary care physicians who think their work has been undervalued.

The median salary for a gastroenterologist was $481,000 in 2011, according to data from the Medical Group Management Association. By contrast, the median salary for a pediatrician was $204,000 and that of a general internal medicine doctor was $216,000. Those kinds of disparities are leading medical students away from primary care, critics say.

“I didn’t know they got that many RVUs [points] for a colonoscopy — that’s kind of amazing,” said Cynthia Lubinsky, a family practitioner in the next county over from Narula. “Do I believe that the payment system is fair? I would have to say no.”

Even if the method that the government uses for setting values is haphazard, however, the question of what doctors ought to be earning is unanswered.

It is an occupation, Narula said, that consumes one’s life.

It has required more than a decade of training: college, medical school, an internship and a fellowship.

He visits patients every day after his work at the surgery center. He does rounds there every third weekend. He is on call every third night.

When the subject turns to fair compensation, he draws comparisons to other lines of work.

“What is the right price?” Narula asked. “Who can tell? A lawyer can charge $400 an hour. My accountant charges me for 15 minutes of time even if he just opens an e-mail from me. And what about the bankers? . . . Ultimately, this is for society to decide.”

No charges against state Arizona Sen. Rick Murphy in sex inquiry

By Mary K. Reinhart The Republic | azcentral.com Wed Jul 24, 2013 11:39 AM

Peoria police won’t recommend charges against state Sen. Rick Murphy in connection with allegations he sexually abused two boys in his care.

In a police report released today, investigators deemed the case “inactive” because one of the teens has recanted, there were no witnesses to any of the alleged incidents and Murphy has refused to be interviewed.

Police and state Child Protective Services launched a joint investigation on June 22, after an older teen reported repeated incidents of alleged abuse by Murphy going back at least six years. The teen also self-reported his own inappropriate sexual contact with another child in the home, according to the police report.

According to the report, the adopted son who made the most recent allegations later “‘retracted’ his statements and is choosing not to speak about either incident.”

Murphy was not interviewed as part of the investigation. The reports quotes his attorney, Craig Mehrens: “On my advice he (Murphy) will respectfully decline an interview at this time. [Senator Murphy is taking the 5th, which is what ANY defense lawyer will tell you to do] In any event all he could tell you is that he has never abused anyone, let alone a child in his care.”

CPS removed the two young foster children living at the Peoria home of Murphy, 41, and his wife, Penny, 48. The couple’s four adopted daughters also were briefly removed June 22, interviewed by forensic interviewers, and returned to the Murphy home. The 18-year-old who made the allegations against Murphy moved out, police said.

According to the police report, CPS told investigators that they removed Murphy’s adopted children from the home last week and a dependency hearing in juvenile court was scheduled this week.

The allegations prompted police to reopen an inactive 2011 case involving Murphy and another boy, a foster child who was 13 years old at the time. According to a Peoria police report, the teen accused Murphy of fondling him underneath his clothing every other day for more than a month and offering to buy him a bicycle if he kept quiet.

The foster child, who now lives at a group home, was reinterviewed by police on July 10 and stood by his allegations.

Taxation Vexation: Phoenix-area home values went down; property taxes stayed up

By Ronald J. Hansen and Catherine Reagor The Republic | azcentral.com Mon Jun 17, 2013 10:55 AM

During the epic housing crash, property values fell by almost 50 percent in Maricopa County. Did property taxes fall a similar amount? Not by a long shot.

As homeowners clung to the idea that lower tax bills would be one small consolation of the bust, schools and cities and fire districts and hundreds of other government entities stared down their own financial crises in the five years from 2008 to 2012.

With property valuations in general dropping by double-digit percentages each year, equally less taxpayer money would be collected. But demands for education, city services and fire protection for essentially the same number of residents weren’t abating.

School boards, city councils and other government entities, scrambling to avoid the full effects of the property-value crash, wielded their power to raise tax rates to collect more money.

The rising tax rates created a vexing disconnect between values and taxes for all property owners, commercial and residential.

For homeowners, the frustration was felt with every payment of every tax bill, even though Maricopa County easily had the lowest residential property taxes among the nation’s 20 most populous counties in a national Tax Foundation survey.

Every year, many property owners expected to receive the bill that would drop in lockstep with their falling property value.

For most people, that bill never came. County residential-property values declined, on average, three times faster than tax bills between 2008 and 2012, according to an Arizona Republic analysis of county data.

Among 970,000 residential properties that were on the tax rolls in those five years, overall property taxes declined 16 percent on average, according to The Republic’s analysis of county tax and property records. Property values plummeted 49 percent over the same period.

This trend generally applied to most houses in the county. But another factor plays into each homeowner’s tax bill: the region’s decentralized tax system, created in the 1980s to allow each taxing body to manage its own costs and to make growing areas essentially pay for their own infrastructure.

Individual tax bills varied wildly — even within adjacent neighborhoods — lending a maddeningly random quality to the system. With a patchwork of school districts, municipalities and more than 1,000 special taxing districts across the county, even houses with identical values could have tax bills that vary by more than 300 percent, according to The Republic’s analysis.

For example, owners of a house assessed at $150,000 in Cave Creek owed $1,005 in taxes in 2012; owners of a house in Laveen with the same assessed value owed $2,361. Owners of a Scottsdale house assessed at $300,000 owed $1,831 in taxes; owners of a Glendale house with the same assessed value owed $4,504.

“During the past few years, many metro Phoenix homeowners have been opening their property-tax bills and thinking, ‘What the hell?’” said Mark Stapp, executive director of Real Estate Development at the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. “Their home’s value has dropped. But their taxes haven’t because local governments have to raise money, even when home prices are down.”

For nearly 150,000 homeowners, tax bills were higher in 2012 than they were in 2008. More than 7,000 homeowners saw their bill rise every year in that span, according to The Republic’s analysis of county records. At the same time, small pockets of homeowners saw their bills drop almost in step with the decline in their valuations. Cave Creek homeowners had among the lowest tax burdens.

Because of higher tax rates, homeowners saw their bills rise in Phoenix’s posh Biltmore area, in swaths of southeast Mesa, in the area surrounding Arizona State University in Tempe, in Ahwatukee Foothills’ newer neighborhoods, in new communities in Surprise and in golf-course communities in north Scottsdale.

Homeowners in lower-income areas often felt the sting of higher school tax rates as values fell and perennially cash-strapped districts raised their assessments. By the end of the recession, residents of the relatively low-income Roosevelt Elementary School District in south Phoenix paid one of the higher school tax rates in the Valley.

Kevin McCarthy, president of the Arizona Tax Research Association, said widespread apathy about tax policy, from city budgets to school bonding issues, has helped create a system in which few people connect their voting decisions to their pocketbook.

“Your property taxes aren’t simply based on the value of your property. They’re based on the budgets of the many jurisdictions that tax your property, and they’re also based on voter activity,” said McCarthy, a lobbyist for commercial-property owners and an expert on the state’s property-tax system.

Property-tax bills are composed of two dozen different categories, some of which can include multiple taxing entities levying taxes annually.

School taxes for elementary, secondary and community colleges make up more than two-thirds of an average property owner’s tax bill, according to Maricopa County officials.

In many — but hardly all — cases, school taxes are the main reason for higher-than-expected bills as districts raised rates to counter the drop in property values. And voters in many districts added to their school taxes by approving overrides — measures that raised extra cash for classroom operations — and construction bonds.

For other homeowners, special taxing districts can be the reason behind their higher-than-expected taxes. Homeowners, often on the region’s fringes, live in newer communities where the developer established special districts to pay for roads, fire protection, water, lights and other services. Homeowners in long-established areas may be part of irrigation or improvement districts they may barely be aware of. Taxes from those districts boost homeowners’ property bills, creating tax gaps between them and others nearby who aren’t in those districts.

Unlike city boundaries or neighborhood signs that help visualize communities for the public, there are no obvious markers for taxing districts. One neighborhood may have multiple tax overrides and bonds to pay for each year, while homeowners less than a mile away belong to separate school districts and pay different special taxes.

It’s rarely the type of detail most prospective buyers check before closing on a home.

While some frustrated homeowners may view the system as a conspiracy to suck more money from their pockets, it may be more fairly viewed as the bill for a la carte government. If roads or lighting or school-spending increases were desired, those in the area, not the broader population, were saddled with the tax expense.

Every year, the county treasurer sends out bills based on tax rates set every summer by every taxing district. Few people challenge the system. Perhaps one reason for that: Compared with California or New Jersey or Connecticut, taxes here are relatively low.

The Tax Foundation, a Washington-based nonpartisan tax-research organization, analyzed nationwide Census Bureau data on property taxes between 2005 and 2009.

Maricopa County’s median property tax in that span was $1,346, slightly less than Pima County in Arizona and 849th highest in the nation. In property taxes as a percentage of household income, the county ranked 1,351 out of about 2,900 counties examined by the Tax Foundation; in property taxes as a percentage of the median home value, it ranked 2,140.

In Scottsdale: Retiree feels bite of system’s disparity

Retiree Jim Stafford, a Scottsdale homeowner on a fixed income, says his taxes increased 22 percent last year for a variety of reasons, including higher city, county and school levies.

“While I fully appreciate and value county services, it would appear a more realistic budget model might be in order for county government to address wild increases year over year,” Stafford said. “My home continues to drop in value, which increases the pain.”

The beginning: An effort to deal with growth.

The simple math of property taxes, and the system created to manage growth, are two keys to understanding tax trends in Maricopa County.

Two numbers are multiplied to create the tax bill: a house’s assessed value, and the tax rate for each of the many taxing districts in which a house is located. Tax rates, not the property’s assessed value, are by far the most important figures in determining final bills.

Across the country, property-tax systems vary. In a few states, including California and South Carolina, property taxes are set by the state. In others, such as Arizona, Georgia and Texas, property taxes are set by county. Maricopa County’s current decentralized property-tax system was created in the 1980s to modernize education funding and cope with the state’s rapid population growth.

Property-tax bills can include two dozen different categories of taxing districts, from schools to water to community facilities districts to specialized categories such as lighting and irrigation. A typical homeowner’s bill has more than a dozen taxing entities levying taxes annually.

That localization means costs often are funneled directly to those who are using the services instead of spreading them citywide, countywide or statewide. The impact of education taxes, and taxes tied to development, can create profound disparities between tax bills.

Built into the decentralized system is the ability to adjust tax rates as needed to provide enough cash for these services regardless of property valuations, McCarthy said. In the boom years of the past decade, tax rates often were lowered to reflect the growing base of property owners and the rising value of their houses.